Who's Who

In 1969-70, English students at Benjamin Franklin Middle School conducted interviews for a publication, Black People Making History in Norwalk. Their landmark class project brought public awareness to the lives and contributions of 37 residents, many of whom had migrated from the South.

Son of a North Carolina native and joined the Norwalk Police in 1970; he rose to be the first black deputy chief in 1983.

Born in De Queen, Arkansas and moved for college “with practically no money or resources.” After serving in the Army, he earned a law degree in Ohio, then a masters from UConn. He honed his skills as a future Norwalk and state politician, school counselor and civil rights leader.

Already a young, vigilant civil rights advocate when he arrived in 1960 from rural Virginia. The student reported that Yates “chose the kind of work he is doing because he was born into the black race. His hobby is working for the liberation of the Race.” Yates became regional chair of C.O.R.E., and rose to national leadership. In 1964 The New York Times reported that the Ku Klux Klan inscription had been painted on the steps of his Elm Street home and drawn on his car door.

Housing & Community

South Norwalk’s Washington Village, completed in 1940, was the first public housing project in Connecticut. In the 1950s the Norwalk Housing Authority built additional complexes, including Colonial Village and Roodner Court

Photo: Ferenz Fedor | No.2725, Local History Room, Norwalk Public Library

In 1938 concerned black parents established the George Washington Carver Center on Ann Street in South Norwalk to provide a recreational and achievement focused hub for minority adolescents.

Carver Center groundbreaking at 25 Butler Street (c.1948-49). In 1975, it moved to its current Academy Street location | From left to right: unidentified man and woman, Nellie Brooks Bagley, Dr. W.H.N. Johnson, Rev. Seawall Emerson, Anita and William Bagley, Jr., unidentified man, William Bagley, Sr. | Courtesy of Anita Bagley Schmidt

Bethel A.M.E. is Norwalk’s oldest African American Episcopal church. In 1989 members repeated their August 1959 march with parishioners proudly walking from their original home on Knight Street to the current sanctuary on the corner of Academy and Merwin Streets

Local History Room, Norwalk Public Library

New Housing Development 2023

The Oak Grove Apartments and Learning Center will be developed by the Norwalk Housing Authority and Heritage Housing on a nearly 8-acre plot owned by the Authority.

The Authority received just under $2 million from a state grant program, and will cover the rest of the $36 million total cost with tax-exempt bonds.

With an existing Norwalk Housing Authority complex and child care center next door, the development will increase childcare options for residents.

The child care space will be 5,000 square feet with two classrooms, a prep space for cooking, a playground and additional flexible areas, Heritage Housing founder David McCarthy said.

“The current learning center here is just too small for the demand the housing authority has for it, and it was also really not laid out to be a learning center. It was originally an apartment,” McCarthy said.

While the center will provide child care, its services include educational programs such as a STEM club, homework help and literacy courses.

Oak Grove is part of the state’s Community Investment Fund, Deputy Commissioner of the city’s Department of Economic and Community Development, Robert Hotaling said.

“The creation of more childcare and youth development opportunities, which not only give kids strong community guidance as they grow but also gives mom and dad a chance to get back to work if they're really trying to do that,” Hotaling said.

The first round of Community Investment Fund programming was approved in December, with 26 projects in 15 municipalities receiving $76.5 million, Hotaling said.....Continue reading at CT Public

Read more about the Community Investment Fund 2030

Work in Norwalk

In the 1950s and 1960s — as labor practices advanced and racial bias lessened — black residents began pursuing careers beyond the marginal offerings of domestic, menial and seasonal work.

Some opened small businesses, others were promoted, and men and women alike broke color barriers in an array of professions and city roles.

Price & Lee Co. Norwalk Directory, 1946 | Local History Room, Norwalk Public Library

SANFORD ANDERSON, who hailed from a Virginia family, was a star student-athlete at Norwalk High School. After serving in the U.S. Navy during WWII, and attending Naval Firefighting School, he returned to Norwalk, then worked for D’Addario Concrete & Asphalt Company. In line for a promotion, Anderson’s supervisors recommended him to the Norwalk Fire Department. In 1959 he became the first black firefighter, and in 2004 the first African American Fire Chief.

Members of the Norwalk Fire Department’s Broad River Company with Deputy Fire Chief Sanford Anderson (second from right), 1977 | Local History Room, Norwalk Public Library

Additional Facts

From 1930 to 1970 the demographics of the black population of Norwalk and Connecticut changed greatly. In 1970 Norwalk reported the highest percentage of nonwhite persons (8.4 %), followed by Hartford (8.1%) and Bridgeport (8%).

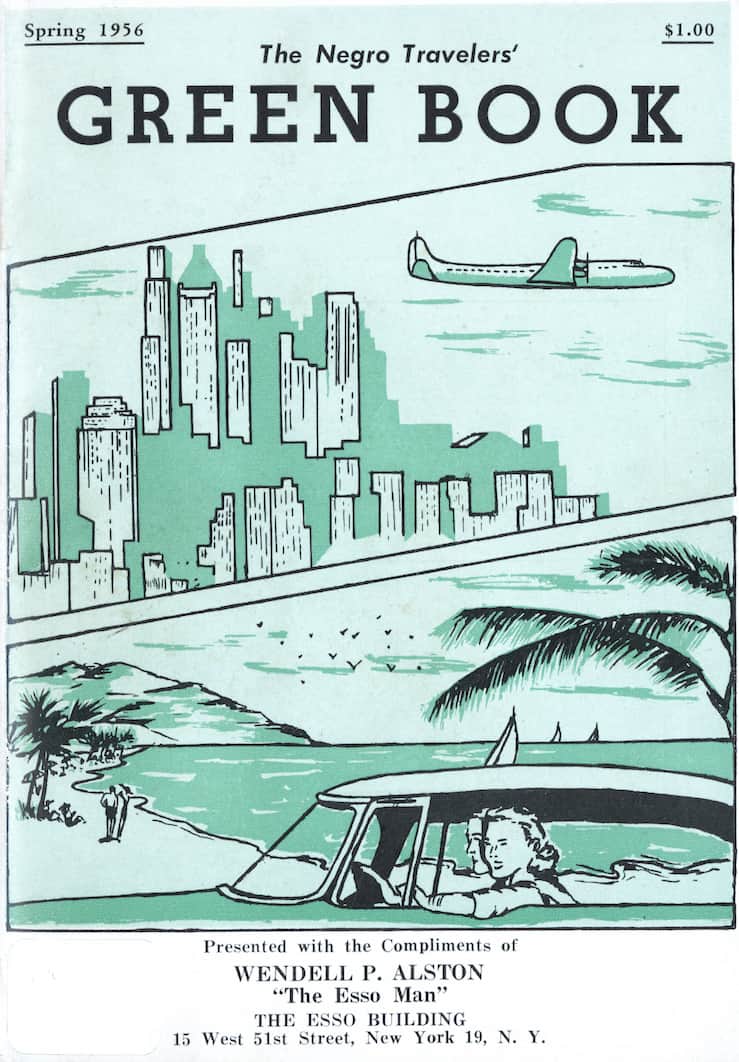

From 1936 until the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Victor Green published this travel guide with hotels, restaurants and businesses where blacks were welcome and safe. The Spring 1956 issue listed South Norwalk’s Palm Gardens Hotel on the Post Road.